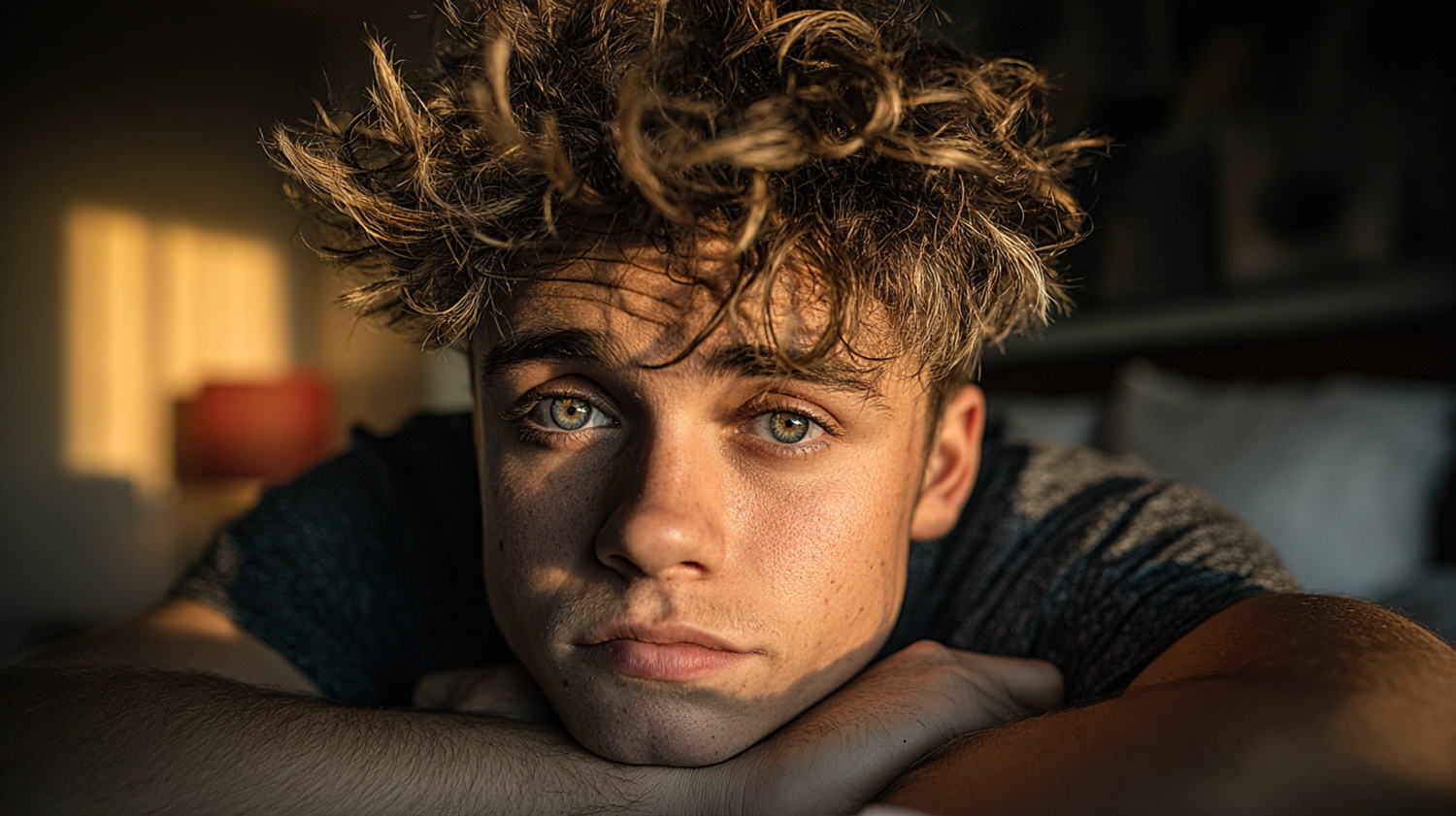

In a world where nearly half of American teenagers describe themselves as being online "almost constantly," schools are facing an urgent question: How do you prepare young people for a digital environment that did not exist when most of their teachers were growing up?

The statistics paint a striking picture of just how embedded technology has become in adolescent life. According to Pew Research Center's December 2024 survey, roughly nine in ten teens use YouTube, about six in ten use TikTok and Instagram, and more than half are on Snapchat. These are not passive users scrolling occasionally—73 percent of teens visit YouTube daily, and 16 percent say they are on TikTok "almost constantly." Meanwhile, cyberbullying rates have more than doubled since 2007, with 54.6 percent of students reporting they have experienced online harassment at some point in their lives, according to the Cyberbullying Research Center's 2023 data.

This is the landscape that has given rise to digital citizenship education—a field that barely existed fifteen years ago and now reaches millions of students through structured curricula in schools across the country. The premise is straightforward: if young people are going to spend their formative years navigating social media feeds, group chats, and an internet flooded with AI-generated content, they need explicit instruction on how to do it safely, ethically, and thoughtfully. But the execution is complicated, the evidence for effectiveness is still emerging, and the challenges keep evolving faster than schools can adapt.

What Digital Citizenship Actually Means

Digital citizenship is one of those terms that sounds self-explanatory until you try to define it precisely. At its core, the concept encompasses the norms of appropriate, responsible, and ethical behavior when using technology. But that umbrella covers an enormous range of skills and knowledge areas: understanding your digital footprint, protecting personal privacy, recognizing misinformation, responding to cyberbullying, respecting intellectual property, and maintaining healthy relationships with screens and social media.

Common Sense Education, the nonprofit organization that has become the dominant force in this space, breaks its curriculum into six major topic areas: healthy habits and media balance; privacy and safety; digital footprint and identity; relationships and communication; cyberbullying and online harms; and information and media literacy. The organization's free K-12 curriculum now reaches 1.2 million educators in 88,000 schools across the United States, including 80 percent of Title I schools, making it the de facto standard for how American students learn about navigating digital life.

The curriculum is designed to evolve with students' developmental stages. Kindergartners learn basic concepts about the "tracks" they leave online through animated characters. By middle school, students are tackling more sophisticated topics like invisible audiences, the permanence of online information, and the social dynamics of self-presentation across platforms. High schoolers engage with questions about data privacy rights, the ethics of AI-generated content, and how to build a positive digital reputation that can help rather than hurt their future opportunities.

What distinguishes contemporary digital citizenship education from the "internet safety" lessons of the early 2000s is a shift in framing. The older approach focused primarily on stranger danger and avoiding predators online—essentially teaching kids to be afraid of the internet. The current model emphasizes empowerment and agency, helping students develop critical thinking skills and healthy habits while acknowledging that technology is a permanent, often beneficial part of their lives.

The Cyberbullying Crisis and How Schools Respond

Of all the problems digital citizenship education aims to address, cyberbullying is perhaps the most viscerally urgent for students, parents, and educators alike. The data is sobering: according to the Cyberbullying Research Center's 2023 study, 26.5 percent of students reported being cyberbullied in the previous 30 days, up from 16.7 percent in 2016. The percentages of schools reporting weekly cyberbullying incidents are highest among middle schools at 37 percent, followed by high schools at 25 percent.

Unlike traditional bullying, cyberbullying can happen anywhere and at any time—there is no escape when the torment follows you into your bedroom through the phone on your nightstand. The anonymity and distance that screens provide can embolden perpetrators, while the potential for harassment to go viral amplifies the humiliation victims experience. Perhaps most troubling, research consistently shows that students who are cyberbullied are almost twice as likely to attempt suicide.

Schools have responded by incorporating specific anti-cyberbullying modules into their digital citizenship curricula. Common Sense Education's lessons teach students to be "upstanders" rather than bystanders—to recognize when someone is being targeted and to intervene constructively rather than simply scrolling past. Students learn the R.E.A.C.T. framework: Recognize that bullying is happening, Evaluate the situation, Act by supporting the target, Communicate with a trusted adult, and Tell someone in authority if needed.

The federal government has also pushed schools toward action through the Children's Internet Protection Act, which requires any school receiving E-rate funding for internet access to educate students about appropriate online behavior, including cyberbullying awareness and response. This mandate has effectively made digital citizenship education a compliance requirement for most public schools, though the law does not specify exactly what that education should look like.

What remains less clear is whether these educational interventions actually reduce cyberbullying rates. A 2023 study published in Contemporary School Psychology evaluated Google's Be Internet Awesome digital citizenship program using a randomized controlled trial methodology—one of the first rigorous evaluations of its kind. The researchers found that students who completed the program showed significant gains in knowledge of online safety vocabulary and concepts, as well as increased confidence in knowing what to do when online problems occur. However, the study found no measurable effect on actual online harassment behaviors or self-reported civility online, highlighting a persistent gap between what students learn and how they behave.

The Misinformation Challenge in the Age of AI

If cyberbullying represents digital citizenship's most emotionally charged concern, misinformation may be its most intellectually demanding. A Stanford University study involving nearly 3,500 students found that more than 80 percent of middle schoolers believed that an advertisement labeled as "sponsored content" was actually a news story. Research published in the British Journal of Developmental Psychology found that children often start trusting unproven conspiratorial ideas around age 14, precisely when they are spending the most time consuming content on social media.

These challenges have intensified dramatically with the rise of generative AI. Deepfake videos and AI-generated images have become increasingly sophisticated and accessible, creating what UNESCO has called "a crisis of knowing itself." Students now need not just to evaluate whether a source is credible, but whether the image or video they are looking at is even real. At the University of Washington's annual MisInfo Day event, hundreds of high school students gather to practice identifying AI-generated faces and learn to spot manipulated media—skills that did not exist as educational objectives even five years ago.

The Center for Democracy and Technology released research in 2024 showing a troubling gap between what students want and what they are receiving. A majority of students indicated that training on discerning AI-generated from human-generated content would be helpful, yet schools are struggling to keep pace with the technology. The research also found disturbing inequities: LGBTQ+ students and students of color were significantly less likely to report receiving guidance on how to spot false or inaccurate information online.

Media literacy advocates have pushed for state-level mandates to ensure all students receive this instruction. As of early 2024, only three states—Delaware, New Jersey, and Texas—require media literacy education for all K-12 students, though California joined their ranks later that year. Delaware's Digital Citizenship Education Act, passed in 2022, represents what Media Literacy Now called a "new high bar," requiring both that schools include media literacy instruction and that the state education agency create specific standards.

The curriculum in this area typically teaches students frameworks for evaluating information. Common Sense Education uses the "S.I.F.T." method—Stop, Investigate the source, Find better coverage, and Trace claims to their origin. Students learn to "lateral read," opening new browser tabs to check what independent sources say about a claim rather than simply evaluating a website on its own terms. These techniques are drawn from research on how professional fact-checkers work, adapted for classroom instruction.

Privacy, Footprints, and the Permanent Record

Every action students take online leaves a trace—from the photos they post to the websites they visit to the searches they type into Google. This accumulating trail of data, known as a digital footprint, has real consequences that many young people struggle to fully grasp. A controversial post from an emotional fourteen-year-old can resurface years later when that person is applying to colleges or interviewing for jobs. Future employers, colleges, and scholarship committees routinely search applicants' online presence, and inappropriate content can close doors before young people even know they were open.

Digital citizenship curricula address this through lessons on both privacy protection and reputation management. Students learn the distinction between "active" footprints—the information they consciously share—and "passive" footprints—the data collected about them without their explicit awareness through cookies, location tracking, and analytics. They practice auditing their own online presence, adjusting privacy settings, and making intentional choices about what they share publicly.

The framing has evolved to avoid pure fear-mongering. Rather than simply warning students that anything they post could ruin their lives, contemporary curricula emphasize that a digital footprint can be an asset. Students are encouraged to think of their online presence as a portfolio or resume, documenting achievements, interests, and positive contributions. The goal is not to avoid leaving any trace online—an impossibility in modern life—but to be thoughtful and intentional about the impression that trace creates.

Common Sense Education's lessons use the metaphor of an iceberg to help younger students understand digital identity: the posts and profiles others can see are just the tip, while the vast majority of data about a person—browsing history, location data, preferences inferred by algorithms—remains hidden below the surface. Students learn about data privacy rights, how companies collect and monetize their information, and what controls they have over their own data.

What Actually Works? The Evidence Gap

For all its widespread adoption, digital citizenship education operates with a surprisingly thin evidence base. A 2022 systematic literature review published in the International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction found that digital citizenship is often used as an "umbrella term" for technology-related learning tasks that fail to actively engage students in practicing responsible digital behavior in meaningful ways. A 2023 evaluation noted bluntly that "there is little evidence available for their effectiveness or long-term impact."

This does not mean the programs are not working—only that the research has not caught up with the implementation. Common Sense Education's own impact report, released in 2024, found that 93 percent of educators report their students have learned digital citizenship skills using the curriculum, and 94 percent of students feel confident understanding the lessons. When educators were asked about the behaviors they most wanted students to develop, they prioritized awareness about sharing information online, safeguarding data privacy, and reducing cyberbullying.

The challenge of measuring success in this field is considerable. Unlike math or reading, where standardized tests can assess knowledge gains, digital citizenship encompasses complex behavioral and attitudinal outcomes that resist simple quantification. Does a student understand what constitutes cyberbullying? That is relatively easy to test. Does that understanding translate into actually standing up for a targeted peer when the pressure of a group chat makes staying silent the path of least resistance? That is much harder to know.

Researchers have called for more rigorous evaluation methodologies, including longitudinal studies that track whether digital citizenship education in elementary school produces better outcomes years later. Some promising research has emerged from countries like Finland and Denmark, which have implemented media literacy education from early childhood and appear to have populations better equipped to identify deception online, though isolating the specific contribution of school-based instruction from broader cultural factors remains difficult.

The Road Ahead

Digital citizenship education faces a fundamental tension: the digital landscape changes faster than curricula can be updated, standards can be adopted, and teachers can be trained. The lessons students received five years ago about evaluating online information did not account for AI image generators that can create photorealistic images of events that never happened. The anti-cyberbullying frameworks developed before the pandemic did not anticipate deepfake technology being used by students to create fake nude images of their classmates—a problem that has emerged at high schools across the country and represents an entirely new category of harm.

This suggests that the most valuable thing digital citizenship education can provide may not be specific knowledge about current platforms and threats, but rather meta-cognitive skills—the ability to think critically about information regardless of its source, to pause before acting in heated online moments, to consider the long-term implications of short-term decisions. Common Sense Education has increasingly emphasized "healthy habits" and "digital wellness" alongside the more concrete safety topics, recognizing that students need frameworks for managing their relationship with technology itself.

The involvement of parents and families also appears crucial. Survey data consistently shows that digital citizenship education works best when it is reinforced at home, with parents modeling responsible technology use and engaging in ongoing conversations about online experiences. Common Sense Education provides family engagement resources, and many districts have begun hosting digital citizenship nights for parents—acknowledging that adults who did not grow up with smartphones and social media may need education too.

The U.S. Surgeon General's 2023 advisory on social media and youth mental health brought unprecedented attention to these issues, calling for action from policymakers, technology companies, researchers, and families. The advisory noted that children and adolescents who spend more than three hours a day on social media face double the risk of mental health problems. This has intensified pressure on schools to address not just safety and citizenship, but the broader question of how young people can develop healthy relationships with the technology that increasingly mediates their lives.

What remains clear is that the stakes are high and rising. The generation currently moving through American schools will live more of their lives online than any generation before them. Whether they navigate that world as thoughtful, responsible, resilient digital citizens—or as overwhelmed, manipulated, anxious consumers of whatever content algorithms serve them—depends significantly on what they learn now. The schools teaching digital citizenship are making a bet that explicit instruction can make a difference. The evidence is not yet definitive, but the alternative—leaving young people to figure it out entirely on their own—hardly seems like a viable option.

Sources

- Pew Research Center. "Teens, Social Media and Technology 2024." 2024.

- Pew Research Center. "Teens, Social Media and AI Chatbots 2025." 2025.

- Cyberbullying Research Center. "Cyberbullying Facts." 2024.

- Common Sense Education. "Digital Citizenship Curriculum Impact Report." 2024.

- Contemporary School Psychology. "The Impact of Youth Digital Citizenship Education." 2023.

- Media Literacy Now. "Media Literacy Policy Report." 2024.

- Center for Democracy and Technology. "Student Demands for Better Guidance Outpace School Supports to Spot Deepfakes." 2024.

- National Association of State Boards of Education. "Advancing Policy to Foster K–12 Media Literacy." 2024.

- Delaware Business Times. "Delaware Takes the Lead on Teaching Media Literacy." 2024. (Source no longer available online.)

- NPR. "AI Images and Conspiracy Theories Are Driving a Push for Media Literacy Education." 2024.

- UNESCO. "Deepfakes and the Crisis of Knowing." 2025.

- Education Week. "Why Schools Need to Wake Up to the Threat of AI 'Deepfakes' and Bullying." 2024.